In Praise of Diafine

Published on 7 April 2022

This is how Diafine was sold when I bought it in 2014

Introduction

In 2014 I came across Diafine, which is a two-bath black and white developer made by Acufine Chemicals in Illinois. Having previously used Kodak’s classic HC-110 it was an eye-opening experience to use a developer which is almost “film and temperature agnostic”.

With Kodak’s eminent HC-110 one has to find the right developing time depending on the particular film used, the ISO at which it was exposed and the temperature of the one’s chemistry (a good starting point is the Massive Dev Chart). On top of this, one has to mix the right amount of developer in relation to the size of one’s film tank to arrive at one’s preferred dilution. And then, if one wants to channel one’s inner Ansel Adams and use the Zone System, one has to adjust timings and dilution depending on the contrast one wishes to achieve depending on how a particular scene or roll was shot.

Please don’t misunderstand me, I think HC-110 is an amazing developer and it is much less complicated to use than the above seems to suggest. But from a usage perspective Diafine is in another league.

Using Diafine

Diafine is very easy to use:

Pre-soak if you like.

Pour in Solution A and agitate a bit. After around 4 minutes pour it back into its bottle.

Pour in Solution B and agitate a bit. After around 4 minutes pour it back into its bottle.

Pour in tap water of roughly the same temperature as Solutions A and B, agitate for a minute and then pour it out.

Fix and was as per normal (see my guide on film development).

These points will be addressed below. Diafine can be used across a wide range ot temperatures – the Diafine instructions say 20-21ºC up to 29ºC or roughly 70-85ºF. It is always used at the same times, about 3-4 minutes for each bath pretty much regardless of which film is being developed. More on this below, but first let’s mull that statement over for a moment – “pretty much regardless of which film is being developed”. This means that:

rolls from different brands and

films exposed at different ISO

can be developed in the same tank and always at the same time and temperature. To be able to develop rolls from different brands or shot at different iSO is very handy for someone, like me, who usually doesn’t develop my rolls as soon as I’ve shot them.

Diafine is designed to add speed to a given film. The Diafine instructions include suggested “exposure indices”, that is, preferred ISOs at which to expose films to obtain optimum results. For instance, APX 100 and Fomapan 100 are listed at 200, Fuji Neopan Acros 100 and 400 at 200 and 640, respectively, Ilford PanF at 80, T-Max 100 at 80-200 and 400 at 500-640, and finally Tri-X at 1000-1600 depending on the Tri-X version used.

In my experience these are but indications and Diafine works with many of these films at other ISO settings, too. Importantly, it also works with other films than those listed, which I show in the albums below. As always, one has to test and decide for oneself if the results are to one’s liking with a particular film at a particular exposure index. Some combinations may not work as well as others. But, depending on the film used, it can even be possible to shoot individual frames of a roll at different ISO settings and get good results provided each frame was exposed correctly. I have used this with the wonderful Kodak Double-X (5222), for instance. That’s pretty amazing stuff.

How does Diafine work?

The reason Diafine allows the above is the two-bath process. The first liquid – Solution A – is the developer agent, which the emulsion soaks up. Since there is no accelerant in Solution A development of the negative will not begin. It therefore doesn’t matter if one overshoots the recommended time.

It is the accelerant in Solution B which starts the development of the image. But because the film only absorbs developer from Solution A according to how various areas of the film were exposed Solution B will never over-develop these areas. Instead it will just let the developer soaked up in those areas run to completion and exhaust. This creates a pleasant “normal-contrast” negative. And again, for this reason it does not matter if one were to leave the film for longer than recommended in Solution B.

There are naturally drawbacks with this approach, the chief one being precisely that there is no way during development to control contrast. I’ve tried 3+3 minutes, 5+5 minutes, 3+5 minutes and probably several other combinations simply because I occasionally forget the film tank for a while. It has no impact on the results. The instructions say that one should actually use 3+3 minutes, but because it takes a while to pour the solutions in and out I’m typically using around 4+4 minutes.

The resulting “normal” contrast is great for a hybrid workflow where a main purpose of the development is to achieve a negative which results in a comparably “flat” or low-contrast scan that preserves as much image data as possible for post-processing. For this Diafine is, I think, quite unsurpassed. The result is typically an image which lends itself well to post-processing because shadows and highlights are well controlled, having developed fully. Any lack of control of contrast during development is easily rectified when one is working with the scans on the computer.

A few points on the use of Diafine

Diafine comes in powder form and must be mixed in two batches before use. I use distilled water and have found that the dilution A powder never seems to dissolve fully regardless of how long I stir the solution. In the end I filter out any remaining powder bits using a stainless steel coffee filter.

The Diafine instructions say that one should not pre-soak films, but in my testing doing so has no visible impact on image quality. All images in the Iford Delta album below and several of the other ones, too, were shot on rolls which were pre-soaked for 1-2 minutes.

The instructions also say that one should not use a stop bath, but instead use normal tap water. I do follow this and have never tried using Ilfostop, which is the stop bath I ordinarily use. The reason is pretty obvious. Diafine lets the developer run to completion in Solution B so there is no developing process to “stop”. With Kodak HC-110 it’s necessary to physically abort development at the right time or the results will suffer.

Diafine is meant to be reused and is consequently exceptionally economical. The volume of Solution A only decreases by the amount that is soaked up by the film. Both solutions may also decrease by what may be accidentally spilt when pouring them in or out. The recommendation is to make a large bottle for each solution. The kit gives enough for a gallon of each solution – that is, about 3,8 litres for us logical metric-centred humans. From these large bottles one fills up smaller bottles which are used for developing. For my chemicals, including fixer and stop bath, I regularly re-use 1-litre distilled water bottles, which I tend to accumulate. As necessary one then tops up these smaller bottles from the large ones. And don’t forget to mark each bottle clearly with A and B to avoid confusion.

Diafine is extremely long-lasting, in fact so much so that combined with the fact that it’s meant to be reused it’s got to be a pretty bad business idea. All of the photos in this article were developed using the batch I mixed in 2014. The photos on Ilford Delta 400 were all shot and developed in March of this year (2022). That’s remarkable longevity. Related to this, though, is that as time passes each solution may begin to contain little annoying sedimentary particles. These can get stuck in the emulsion and create a royal pain when dust spotting. I recommend filtering each solution before use with a metal coffee filter (as described in the film development article).

❗️Finally – and this is critical – not even one tiny little bit of Solution B must enter Solution A. If that happens the entire batch of Solution A will be destroyed.

A word about agitation

I’ve found that the agitation technique does not make much of a difference. With for instance HC-110 one typically agitates the first 30 seconds and then a few inversions for 10 seconds every minute. The results will vary depending on how often, long and vigorously one agitates.

The Diafine instructions recommend to initially agitate gently for 5 seconds and then for 5 seconds every minute. This is more or less what I do though I’m not too rigorous. I basically just invert the tank a few times every minute to make sure the solutions swirl around. But one’s style of agitation – mild vs less mild – should not have any greater effect on the results. I would avoid to shake the film tank though; we’re not making James Bond a dry martini here.

Where do you find it?

Unfortunately, Diafine seems a bit difficult to find these days. As the time of writing, it’s in stock at Freestyle Photo and Blue Moon Camera in the United States and at Fotoimpex in Germany. It’s out of stock at most other places. There is, however, a liquid two-bath developer called Bellini Duo Step, which supposedly was inspired by Diafine and is meant to give similar results. I have yet to try it myself, but hope to do so in the future.

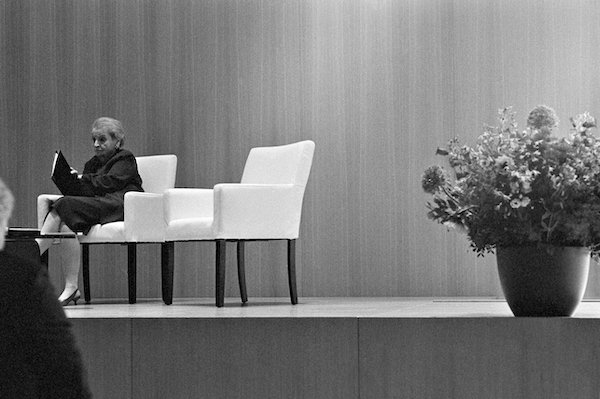

Examples

I’ve used Diafine over the years with films from several brands. In many cases I’ve pushed or pulled the films. I’ve also used it on Kodak T-Max films and the equivalent Ilford (Delta) and Fuji (Neopan Acros) emulsions. According to received internet wisdom, this is supposedly a bad combination, notwithstanding the fact that the Diafine instructions do mention Kodak T-Max. I’ll let you be the judge of the results.

To simplify, I’ve arranged the photos by emulsion. The caption of each photo will say which particular film was used and how it was exposed. If there’s a Flickr link you’ll be able to view the image in high resolution to do some good old-fashioned grain peeping. For a few emulsions I’ve deliberately included several photos shot at the same ISO to hopefully give a good view of how things like highlights and shadows look under different lighting conditions.

Summing up

Well, there you have it. Diafine is a wonderful developer for black and white film. It’s easy and very flexible in use, exceptionally economical and long-lasting, can allow you to change ISO on a roll of film much like one would with a digital camera, and gives negatives which are easy to scan. What’s not to like? Probably only that it’s a bit difficult to find at the moment, but hopefully that will change.