My most recent project – The Tribunal – recently went live. It is a project with which I have worked for quite a long time, several years in fact, and which means a lot to me personally.

The project arose out of curiosity as much as of necessity.

While the ICTY began to be “downsized”, as it is so beautifully called in management speak, and its premises on Churchillplein 1 in The Hague bit by bit were being repurposed, I wondered what it would look like if photographed. As I wandered the corridors during the last few years of the ICTY’s existence I started thinking about the institution as a photographer, and not as someone who was only working there.

I’m quite sure other photographers know precisely what I mean by that. There are times when one keeps looking at the light, paying attention to details, obstacles, angles, stories to be told. And there are other times when one doesn’t. At my ordinary place of work, I would not normally see like I otherwise do. In fact, it’s probably the only place I don’t observe my surroundings in that way.

A crucial question soon arose which needed to be resolved to make the project happen – how to get permission to photograph. It was a United Nations institution, after all. It turned out that I needn’t have worried. From the start my idea was met with interest from the three principals of the institution, President Carmel Agius, Prosecutor Serge Brammertz and Registrar John Hocking. The same interest was shown by the many heads of section whose support was crucial for me to gain access to areas that were off limits even for most who worked at the institution.

As I continued to spend time in the building I consciously and purposefully analysed the areas I went to – offices, the courtrooms, meeting rooms, even the lavatories and the basement – from the perspective of how would I photograph them. Obvious things like lens and film choices were part of this intellectual exercise, but also more complex and intangibly artistic things, like where should or could I put my tripod and how should I expose the film and focus the lens in order to give the viewer the feeling of actually being at a particular location.

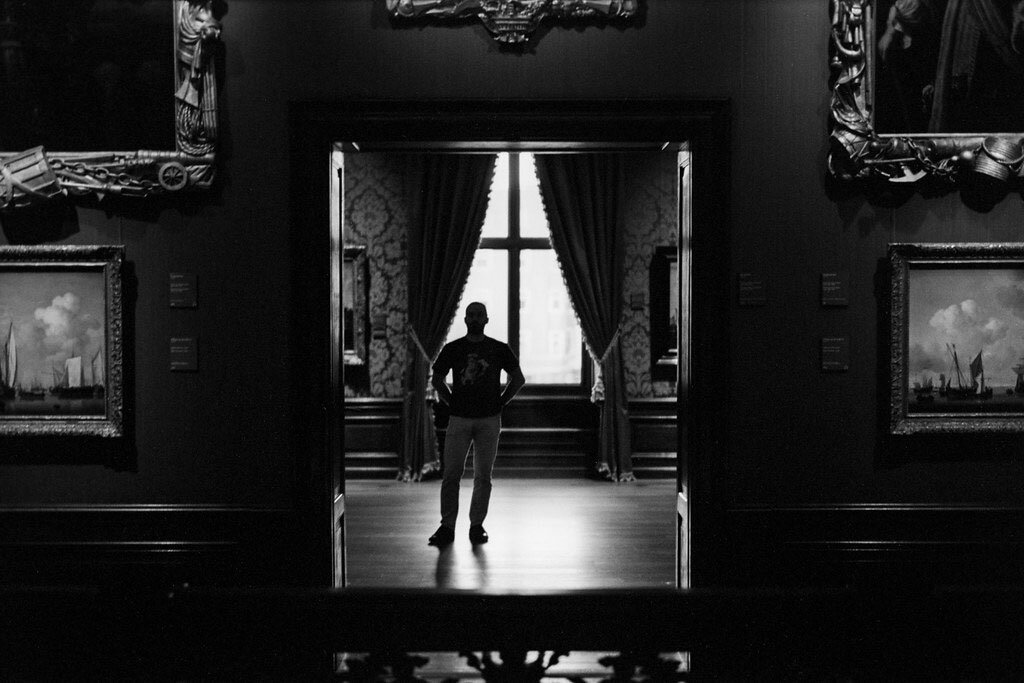

This – presence – has been my goal all along.

The ICTY, like several other similar ad hoc international or internationalised jurisdictions, was finite from day it was born in 1993. It had a set, if at that time unknown, lifespan much like every living thing on this planet. It was never meant to deal with all the war criminals in the Balkans, but only with the most senior accused responsible for the most serious crimes. By default, a heavy burden was always meant to rest on national legal systems in addressing the thousands of persons who committed horrible crimes during the conflicts.

I saw this time-limited aspect of the Tribunal’s existence as a major reason to preserve it for posterity. This is one of the most powerful aspects of photography, in my view. It is a way to literally and visually travel in time, to relive past events. Connected with this is the possibility to give the viewer the feeling of being present inside the frame. Naturally, it depends on what has been photographed and how this was done. A glossy fashion photo, for instance, rarely invites viewers to feel as if they’re “there” on-site. Quite the opposite, actually. Fashion photography seems to actively try to keep the viewer outside and away, much in the same way that certain types of authoritarian photography have been used by less benevolent regimes to distance the leadership from the populace.

Ansel Adams’s supposedly quipped that “'there are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer’. An image can be understood or interpreted, felt even, very differently by the viewer when compared to what the photographer meant. In my view Adams kicked in an open door, but he also alludes to another dimension of the photograph as an interface between the photographer and the viewer, between the vision and the viewed. An image can bring the viewer along for the ride. Some of Adams’s own landscape works achieve this, especially his more intimate photographs of the natural world. To the contrary, at least in my opinion as one of the two people he referred to, his large scale landscapes scenes lack that immediacy. When I see Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite, I feel like I am outside the frame looking in, mouth agape naturally, rather than being there in front of this mesmerising scene. I do not feel like I am part of that scene.

As part of the preservation effort, which this project seeks to achieve, it was important to me that the viewer would feel present in the spaces I photographed. I wanted these spaces to speak unhindered back to the viewer, and I wanted each viewer to feel something in return, as if the viewer had stood where I put the camera. To attempt to realise this vision I chose to photograph the project on medium format film (Kodak Ektar 100 to be precise) bar a handful of shots which are cropped 35mm film. I opted for the square format because in my view that better resembles the human vision; we do not see rectangularly. I also opted for a 40mm lens, which gives a very wide field of view. In some confined locations the choice of lens was due to sheer necessity to be able to get a useable photo. But in most locations this choice meant placing the camera quite close to what I wanted to photograph because otherwise everything would have looked too small. To further strengthen the feeling of presence virtually all scenes are photographed with the camera ca. 150cm above the ground. It is my hope that this will give viewers, regardless of their individual height, a feeling of observing the details of a scene as if they had stood where the camera was placed.

It will be for others to tell if the photos achieve this, of course.